After the Strike

A study of the long-lasting effects of an Israeli Air Force strike on a family’s courtyard in Beit Hanoun, Gaza, Palestine.

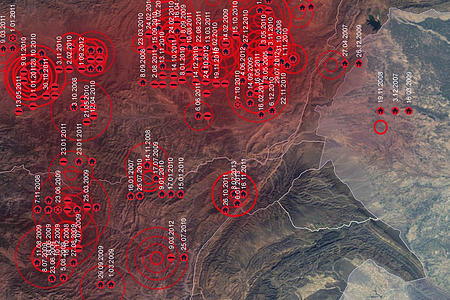

Over the 11-day-long escalation from May 2021, the Israeli military struck Gaza over 1,500 times. Many of those strikes led to significant injury and loss of life, with one of the most deadly attacks killing 44 civilians. Others were less deadly but caused considerable damage to the infrastructure of the Gaza strip.

One such strike occurred on May 14, 2021, when Israeli missiles targeted a courtyard in the town of Beit Hanoun, located in Northern Gaza. The strike immediately flattened a small grocery store and damaged several surrounding buildings. But each and every missile strike triggers a series of events that continues long after the news cycles move on. Following the aerial attack, journalists from The Associated Press (AP) documented the impact of the strike on the Nassir family, long-term inhabitants of the site. Our team worked in collaboration with AP to create a video analysis and reconstruction of the days and weeks that followed the strike. Our intent is to bring attention to this less reported on, ‘slower violence’ that inevitably accompanies military airstrikes in a dense urban context. We have come to define ‘slow violence’ as the aftershocks of an attack: the prolonged process of demolition, clearing, and repairs to the built environment that must happen before life can return to ‘normal’ for the inhabitants. We trace this story of slow violence and its increscent toll on the Nassir family as they were forced to piece their homes and lives back together yet again.

Read the full AP article here.

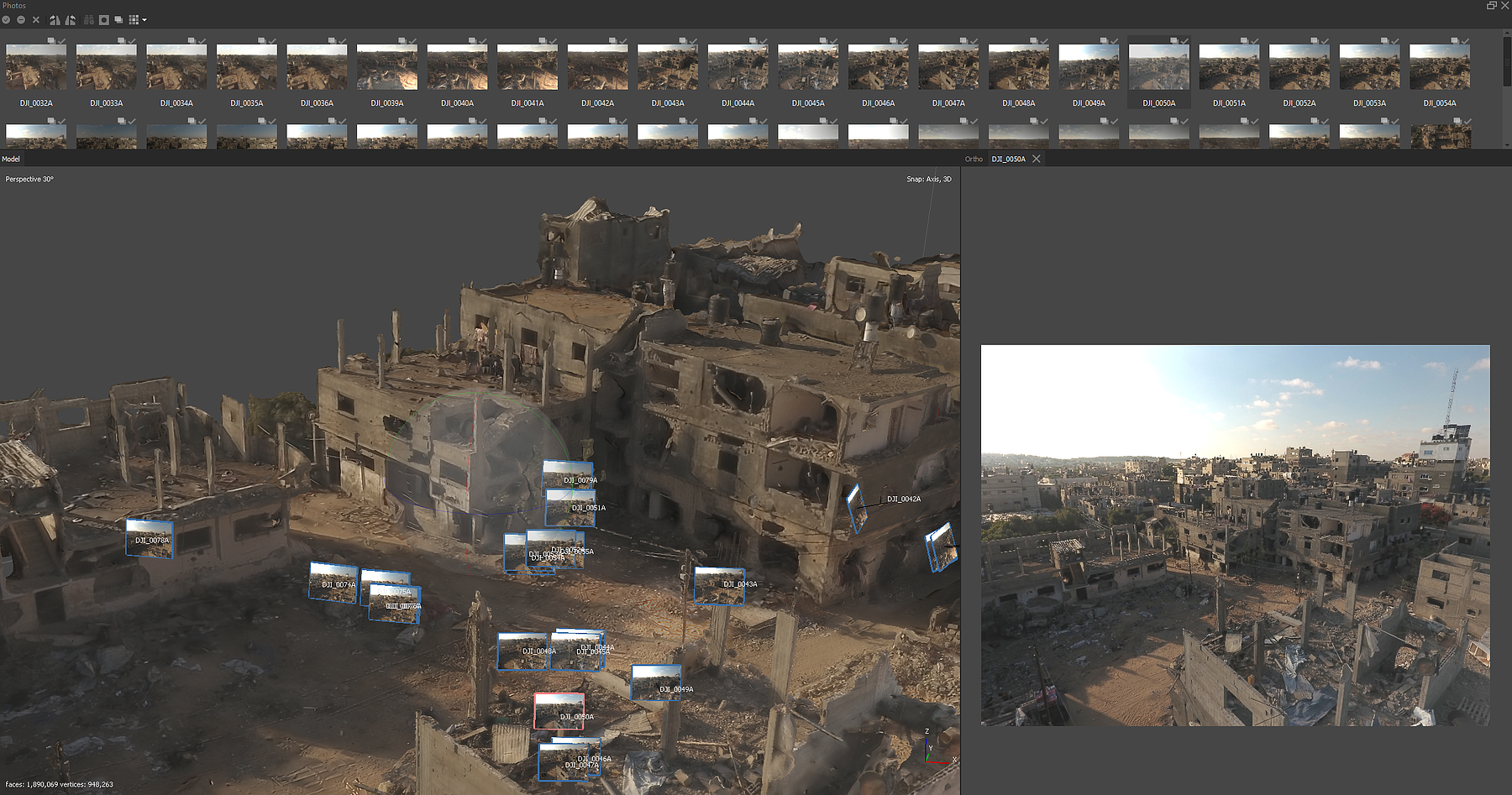

Central to our analysis was the creation of a digital model of the Nassir family courtyard, based on high-resolution drone footage captured by AP videographers, we created a photogrammetric model of the courtyard as it stood a month after the strike. Using photogrammetric techniques—which allow us to derive three-dimensional forms from two-dimensional imagery—we reconstructed a model of the courtyard as it stood one month after the strike. The final model presents a virtual view of the demolished space in a way that faithfully captures specific colors, textures and details of the site as of mid-June, 2021. In the video, this model acts as a spatial framework to situate the recorded testimony of Nassir family members. In navigating this destruction, we are able to present the neighborhood not only as a site of attack but also a site of domesticity and everyday life. Viewers can understand the courtyard as they would any other 3D views such as on Google Earth, and therefore get better acquainted with life amongst the wreckage.

The team wanted to supplement the evocative testimony of the Nassir family with a clear and sequenced account of efforts to rebuild the courtyard, underscoring both the emotional and physical labor Palestinians must undertake after each strike. To establish a clear timeline of the structural changes made to the courtyard after May 14, we worked with Berkeley’s Human Rights Center to conduct open-source research via social media platforms and the AP’s extensive archive to find more footage of the site. We created a 3D representation of the courtyard before the strike in Blender using photographs as reference. We use this pre-strike clay model in the video to clearly reconstruct the sequence of clearing out the rubble, replacing damaged infrastructure, and demolishing buildings that the aerial attack rendered structurally unsound. It was important to stage this reconstruction in the 3D clay model rather than the photogrammetric model in order to emphasize the fact that this cycle of demolition and reconstruction is not unique to this strike nor this courtyard in Beit Hanoun. Rather this is a ritual that has been inflicted on thousands of Palestinians for decades.

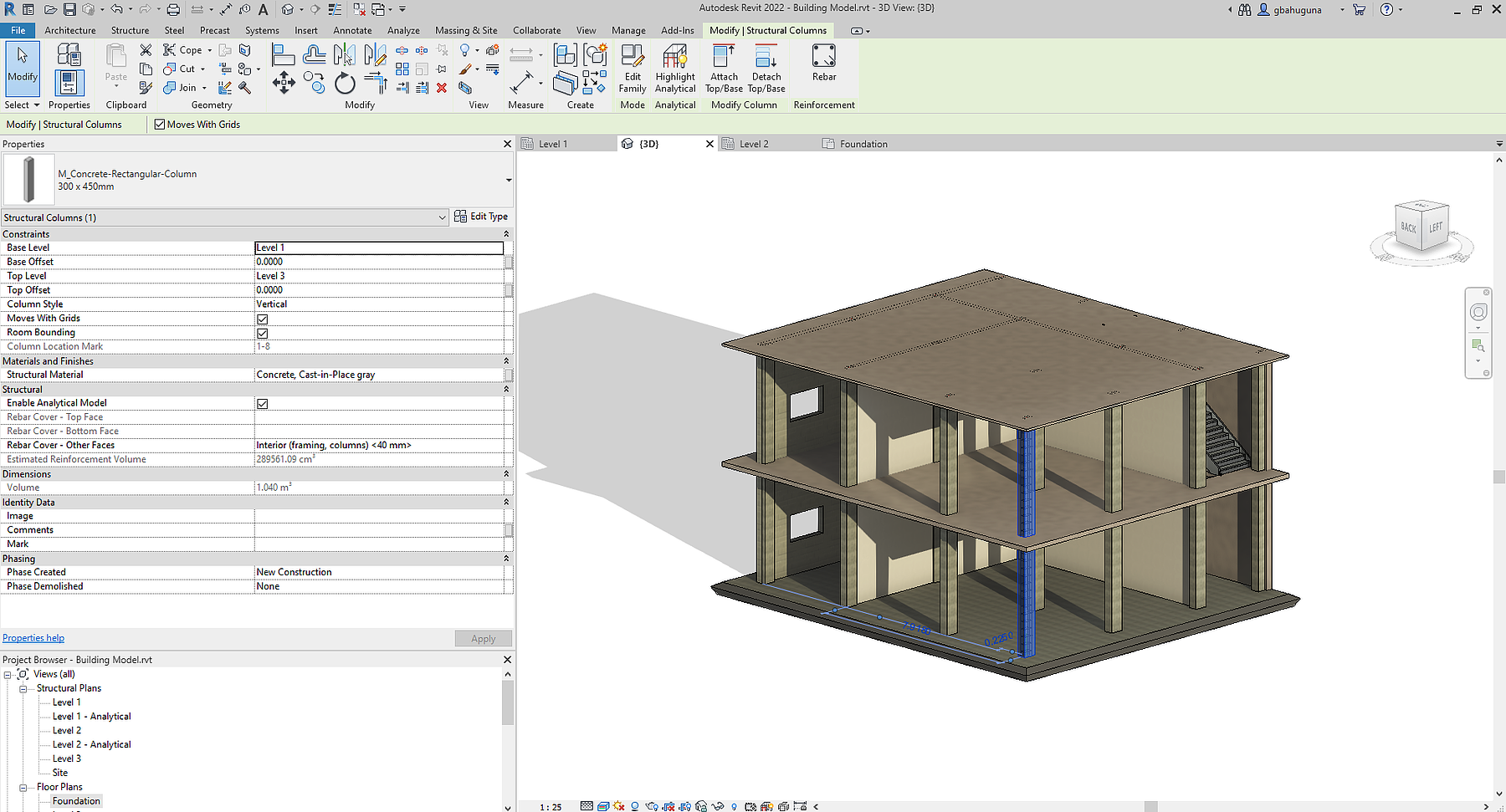

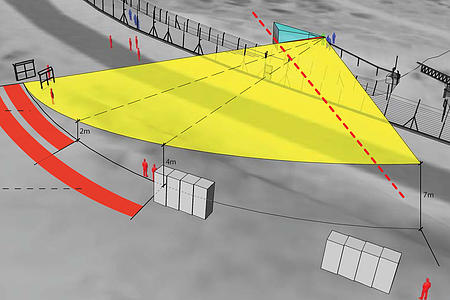

The final component of the video was an analysis of the amount of rubble created during each war in Gaza. We acquired a data set from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) that listed the amount of rubble, in metric tons, cleared by the organization during each of the four most recent wars. Each ton of rubble represents a destroyed home, hospital, neighborhood - an upended life. We wanted to represent the volume of rubble generated by the wars in a manner that was both clear and more humanized than a simple large numeric value. Drawing from our team’s architectural experience and the AP’s extensive documentation of the site, we created a Building Information Model (BIM) of the first building that was demolished in the Nassir courtyard following the May 14 strike. BIM software is commonly used by architects, engineers, and contractors during construction to cooperatively detail a building’s structure and systems. In this instance, the team instead made use of BIM to reconstruct the demolished building with greater architectural specificity, including components like walls, stairs, and windows. The use of BIM allowed the team to coordinate with engineers who advised on likely materials and components utilized for the demolished building. Information about the building materials, their respective densities, and volume of each component allowed us to calculate the total mass of the building. We then compared the mass of rubble produced by this single building to the total rubble cleared by the UNDP in the four most recent wars in Gaza. The analysis was then visualized into an infographic which spatially anchors the BIM model of the demolished Beit Hanoun building inside of the photogrammetric model of the courtyard, drawing clear spatial and quantitative relationships between the destruction of a single home and the scale of destruction across all of Gaza.

With this project, we hope to bring attention to the under-recognized aspect of asymmetric warfare in Israel and Palestine: the enormous human and economic costs of the cycle of demolitions, clean-up, and reconstruction that ensues from this conflict—even from ostensibly ‘surgical’ or ‘targeted’ military interventions.