Museum of Modern Art: Invisible New York

SITU’s work for the Uneven Growth exhibition at MoMA focuses on the informal component of New York City’s housing market and seeks to place it squarely within conversations about affordability.

Client

Collaborators

Cohabitation Strategies, Citizen's Housing and Planning Council, Jesse Keenan (CURE)

Location

New York, NY

Completion

2014

Photography

In the exhibition, SITU presents research findings as well as a series of design strategies that seek to merge bottom-up and top-down responses to unevenness in New York.

Our contribution to Uneven Growth addresses the hidden density of New York’s informal housing not by trying to shift residents elsewhere, but rather, by proposing a way for communities to thrive within the neighborhoods they already inhabit. By focusing on tactical interventions, additions and renovations of existing housing stock, we envision a landscape of accretive architectural proliferation that populates rooftops, backyards, industrial buildings and other available spaces. Research for this project focused on approaches to hidden density in New York City though ethnographic and data-driven methods, investigating informal housing arrangements like illegal conversions, cellar dwellings, shared spaces, single room occupancies (SROs or flophouses) and three-quarter houses.

Governed by a unique “Right to Shelter” mandate, New York is distinct from other municipalities across the U.S. in its legal provisions for temporary housing assistance. While this constitutional right may provide some relief for homeless New Yorkers, the extra-legal reality is that the cost of shelter has forced far greater segments of the city’s population into informal housing markets—a condition that is at once pervasive and hidden.

Because this segment of New York’s population is packed into housing stock that is completely at odds with contemporary demographic realities, the informal markets have carved up and occupied the interiors of the city in order to create viable housing options. Concealed within the city’s seemingly endless rows of apartment buildings, townhouses, and high-rises is a network of typologies that have adapted, subdivided, or converted existing spaces to accommodate the growing number of those who cannot find a place within the formal housing market. Existing somewhere between the designation of “homelessness” and the “lowest income” of the affordability ladder, this population works in the lowest paid jobs. Most frequently they are employed in the service sectors providing the support necessary to keep this so-called ‘luxury city’ upright and thriving.

While it is precisely these informal networks that most readily propagate the evidence of uneven growth in New York, it is, by definition, a condition that resists measurement. The 2010 Census results for New York City yielded highly contentious results—by some measures undercounting by 200,000 people. These omissions were particularly acute in parts of the outer boroughs with the highest concentrations of illegally converted apartments. Whether the evidence is anecdotal or gathered by virtue of proxy indicators (i.e. utility consumption per square foot or Building Department violations), it is certain that the informal housing market is pervasive in certain neighborhoods in Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx. This reality points to the fact that the quality of life that so many New Yorkers have become accustomed to relies upon the services provided by a sizable population whose presence is rarely acknowledged or discussed. The network of Three Quarter houses, cellar units, illegal subdivisions, and flophouses that constitute this foundation conceal a significant number of citizens. In their invisible state, they are left out of the discussions, policies, and design decisions that shape the city in which they live.

Politicians and researchers have argued that in the most recent decennial census, conducted in 2010, New York City’s population was undercounted by upwards of 50,000 and perhaps as high as 400,000 people. Much of the discrepancy is believed to have occurred in communities within the boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn—vibrant neighborhoods such as Astoria and Jackson Heights, Bay Ridge and Bensonhurst—that experienced high population growth between the 1990 and 2000 census. An undercount of this magnitude results in a wide gap between community needs and city funding for key initiatives such as affordable housing and transportation—calling into question the accuracy and practicality of the decennial census.

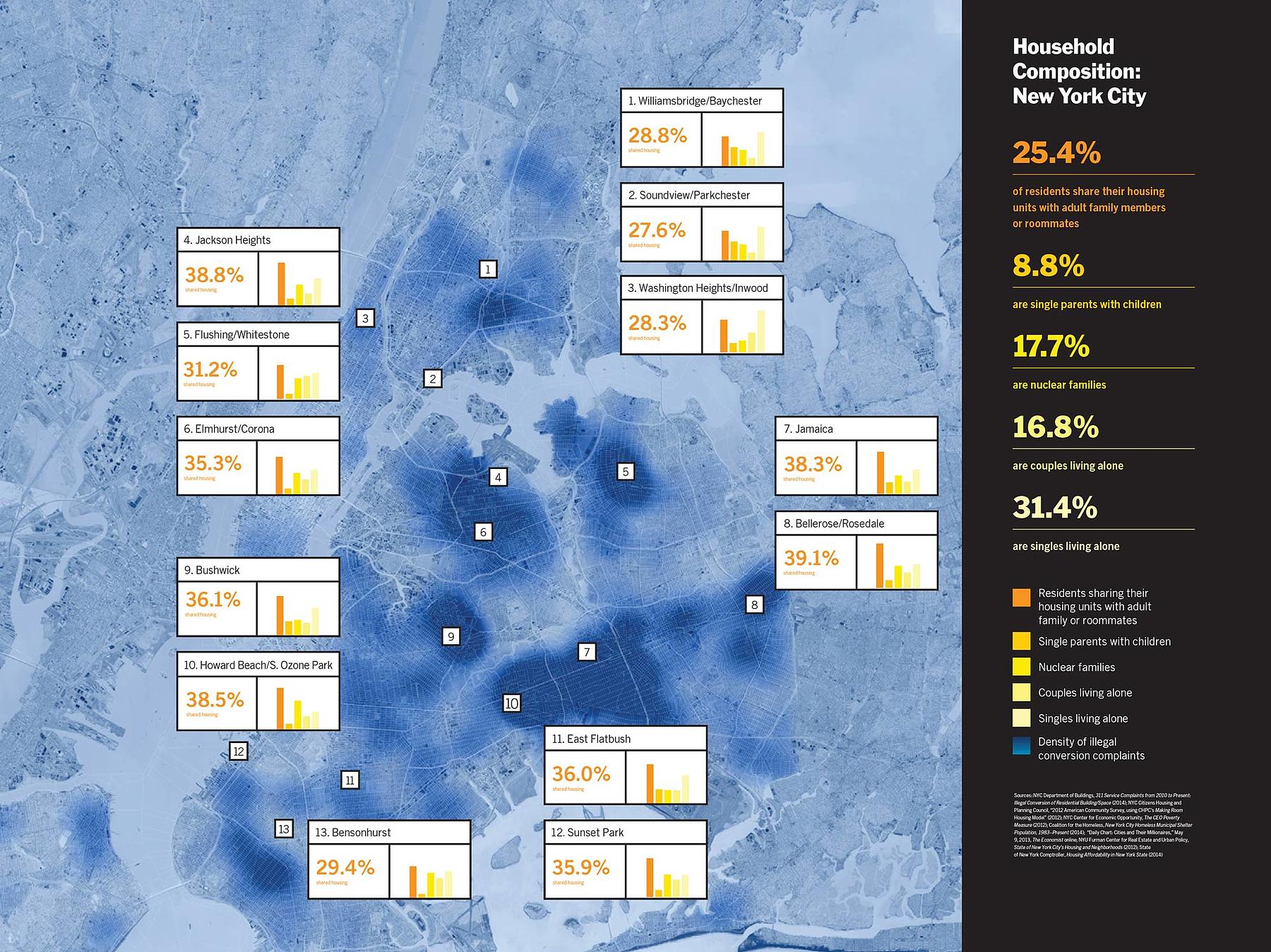

For Uneven Growth, SITU worked with the Citizens Housing Planning Council to visualize data from the American Community Survey with respect to housing demographics. The above diagram shows the 13 neighborhoods in New York City with the highest rates of shared spaces per 2012 ACS data. When superimposed on the map to show locations of reported illegal conversions (in blue) a correlation can be seen between concentrations of informal housing and shared living conditions. Citywide, only 17.65% of housing units are occupied by what the Census Bureau considers “nuclear families.” However the City’s housing stock consists largely of 2-3 bedroom apartments with a “master bedroom.” This disconnect between demographics and existing typologies provided an important starting point for our exhibition research.

Overall, the percentage of singles living alone is 31.4% and the percentage of housing units that are shared either with or without family members is 25.4%. Given these trends, SITU focused on strategies dedicated to realigning living space and demographics realities by focusing on the needs of individuals living alone as well shared housing arrangements. In this sense, The Other New York focuses on a model of incremental growth and flexibility in the type of housing stock as a direct response to the shifting demographic trends within neighborhoods expressed in the American Community Survey.

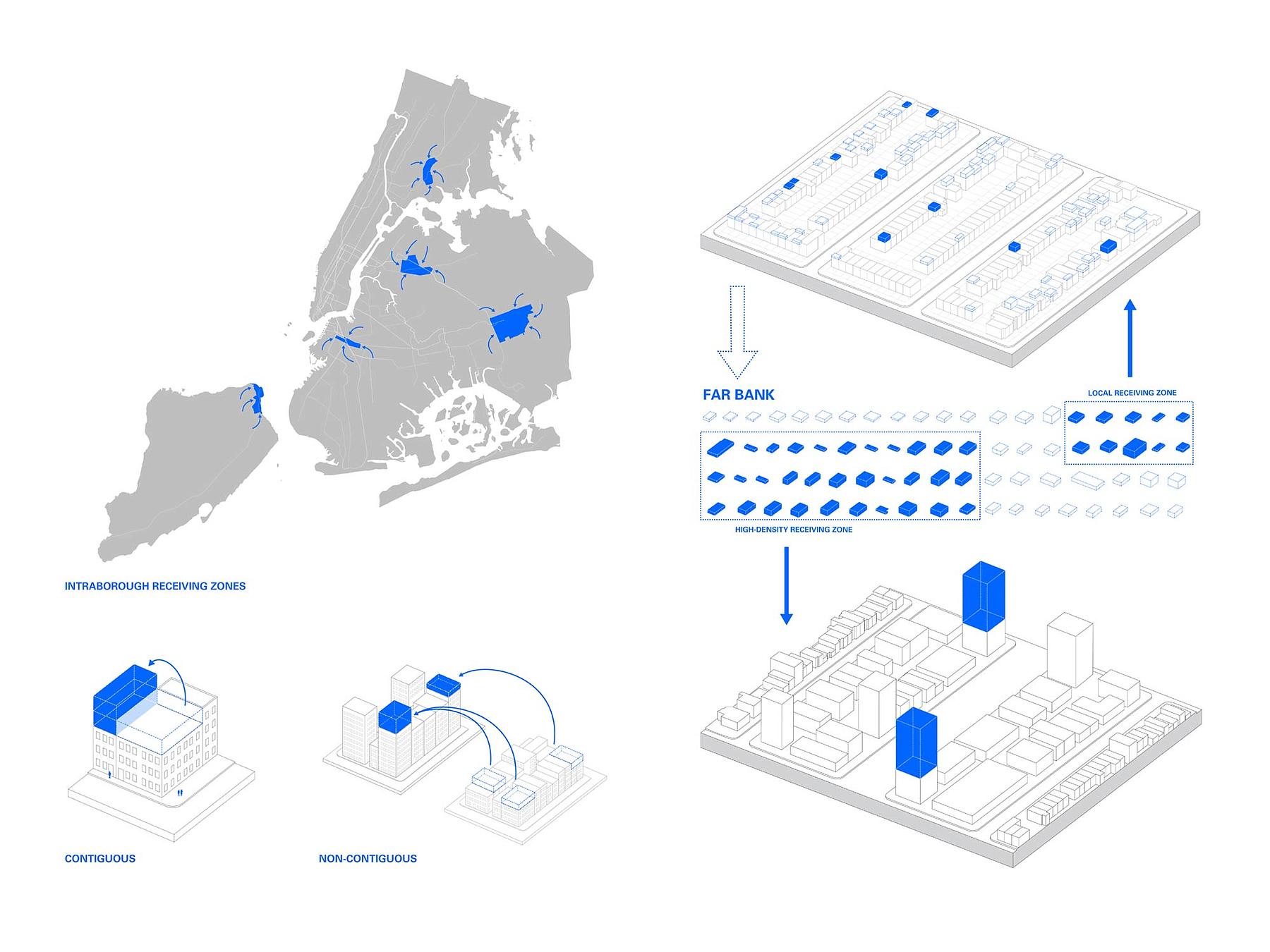

As part of its research for the Uneven Growth project, SITU worked with Jesse Keenan of the Center for Urban Real Estate (CURE) to propose an ownership and development model focused on capturing the value of unused air rights in the service of funding affordable housing. In addition to working closely with Jesse, the Furman Center’s guidance and work on Transferable Development Rights was an essential component of this research. This post focuses on SITU’s strategy for unlocking development rights as one approach to addressing the affordability crisis in New York on a localized level. The CGC proposes a scenario where underutilized urban spaces could be opened up to a new type of incremental growth facilitated through neighborhood based organizations called Community Growth Corporations.

The Community Growth Corporation (CGC) is a hypothetical development model meant to align social and financial capital in a way that allows for the preservation of affordable housing and the creation of community-driven neighborhood projects. The mechanism for capitalization is a public auction of excess floor area ratio (FAR) within a community that would otherwise go unused, or where the cost to build to the FAR outweighs the benefit of added interior space. Excess FAR is then exchanged for a share of the CGC. Altering the existing regulations so that FAR is no longer restricted to contiguous properties, but instead can be aggregated—forming new kinds of development—both low-rise affordable housing or higher rise mixed-income developments in adjacent neighborhoods that are suited for denser development.

“Receiving Zones” are identified as areas that are capable of accepting increased density due to the availability of space as well as existing access to transportation infrastructure. “Donating Zones” are identified as areas that are currently over-populated and are severely rent-burdened, meaning that on average households spend more than 50% of their income on housing. The transfer of FAR between the two zones can only occur if they are adjacent.

By exchanging excess FAR for shares in the CGC, landowners of properties with affordable housing receive modest investments returns that must be used to renovate or further develop the property. These returns are attached to the property itself rather than its owner in order to ensure that investment in affordable housing is continual, especially in neighborhoods that are already over populated and rent-burdened. All residents are able to gain shares in the CGC, regardless of whether or not they are landowners, through “sweat equity”—participating in street and public space improvements, engaging in senior care activities, coordinating transit pools, etc. Returns for these CGC shareholders come in the form of unit renovations or as rent credits, ensuring the advancement and quality of affordable housing.